Finishing the studies on time?

Finishing the studies on time?

Most students get through their studies without a fuss, landing safely in the claws of work life. But a bunch of students need more time. Why? Do we like student life so much that we delay entering the life of adults?

Journalist: Åsmund Godal Tunheim

Translator: Ingvild Sperstad

Illustrator: Eva Weston Szemes

Thorvald with a straw in the money of the state

As Norwegian students, we are blessed with the principle of free education. The state finances our education, in addition to supporting our living costs through stipends and loans. This system is a huge investment in knowledge, that hopefully will be profitable through all our years in the workforce.

But with this principle comes catches: You have to be a citizen of a European country (we will leave this discussion for another time). You also get stipends and loans for a maximum of eight years, where you have to do 60 credits a year. The state also reserves the right to 38% of your stipends until you have finished your degree on time, not including single-year study programmes. And lastly, for every year you study and live off of these loans, your debt keeps growing.

Number crunching

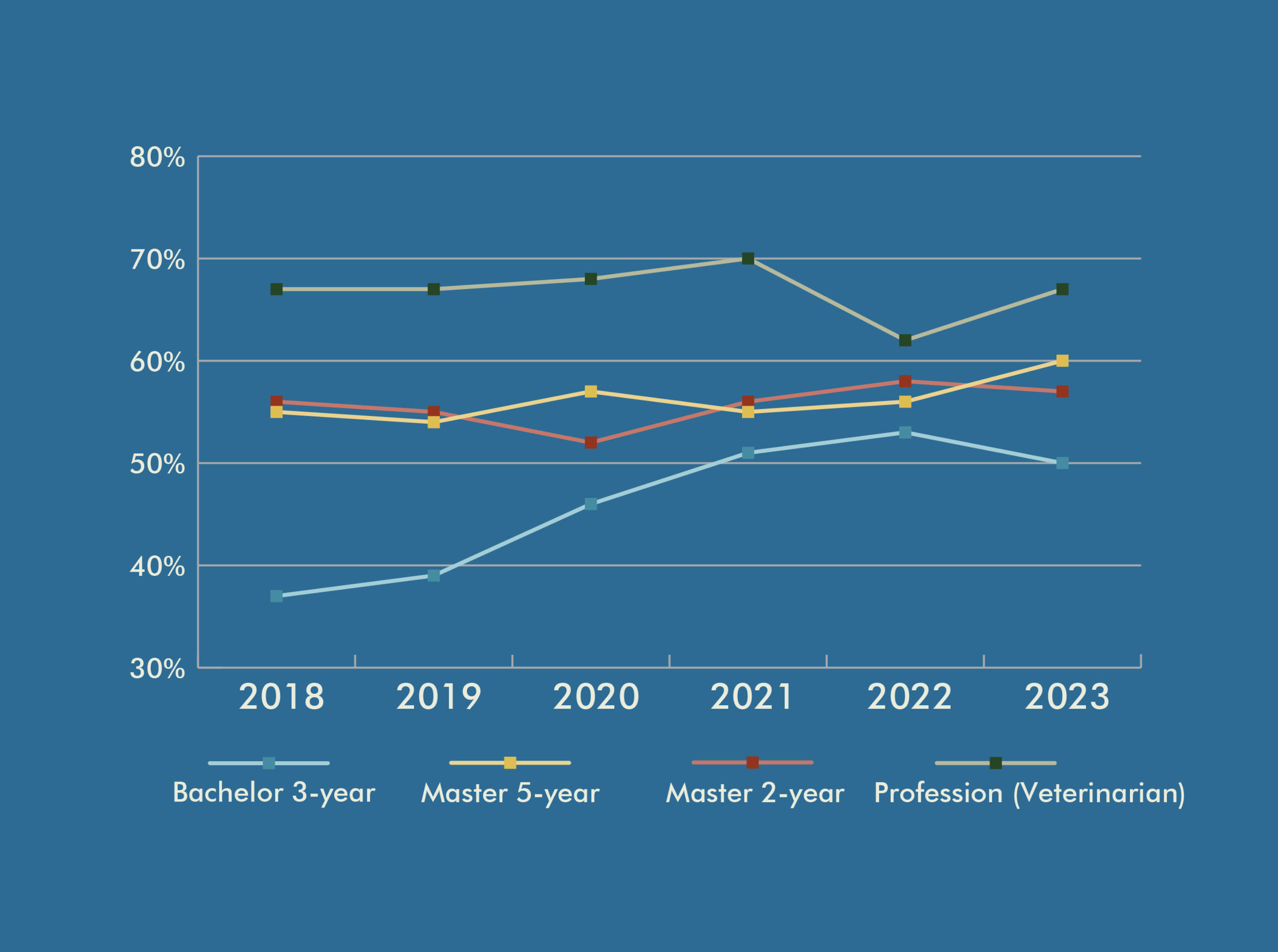

Even with all these incentives to finish your studies, a lot of NMBU-students choose to take their time. Actually, only around half of the students starting a bachelor's degree will finish in the standard time. About 15% quit NMBU during their studies (most of them in their first semester), and 10-15% switch their study programme. Excluding these, around 70% get their degree on time, and 30% spend one or more extra semesters. At Master level, the amount finishing on time is slightly higher, and it’s highest for Veterinary medicine.

Reasons for delay

As mentioned earlier, a substantial number of students do not follow the ordinary study plans. Ole-Jørgen Torp and Knut Løvold at the study department work on collecting and analysing these numbers. They say that NMBU does not stand out much compared to other universities, and that the reasons submitted by students are many and varied. Some quickly realise the studies are not for them. Others have kids, go through break-ups or have physical or mental challenges that make it difficult to complete mandatory assignments.

Distractions outside of the reading hall?

Then there are the ones that seem to enjoy themselves way too much. The ones at Bodega every Wednesday, join two or three associations, get involved in UKA or Samfunnet, in the student democracy or in some advocacy group. Ås is well known for its strong culture for getting involved outside of the books, and here, people sacrifice huge numbers of hours. But can this involvement also take the focus away from studies, and make more people fail exams and postpone their degree? I have a chat with SiÅs’ student life coordinator Marit Raaf, who works on accommodating health and well-being among students. She says that contrary to the picture of “everyone” joining some kind of organisation outside of their studies, this is only true for 43% of students.

Marit does not necessarily agree that the student involvement negatively affects the studies, rather the opposite: “Getting involved in things outside of your studies is a nice way to disconnect, and it gives you energy. If you have a lot of things you want to do, you get more effective”, she says. She points out that volunteering is a positive resource that gives students a social network they can enjoy. Finding other students with similar interests, to find a team or an organisation where you can feel useful, can positively affect the well-being and completion rate of students, she thinks. She also sees that some students are overwhelmed by the number of positions they take on, and in those cases, she advises them to adjust the amount of extra commitments outside of their studies.

Economy as a factor

Oskar Solberg Lægland, Head of The Student Board, agrees with Marit that student volunteering is a positive factor. According to him, economy is a much bigger obstacle for the completion rate. A lot of students have to work on top of their studies to make ends meet.

Oskar emphasises the fact that the people in charge on the one hand give us incentives to finish as quickly as possible, and on the other hand give us less and less money in practice. “Students in this country work on average around 10 hours a week. This can affect how quickly you finish your degree”, he points out. He also emphasises the new suggestion to make students pay if they want to resit an exam to get a better grade, and that this can make people “strategically fail” exams if work, other commitments or life itself make schoolwork difficult. This can delay your degree, and is also a breach of the principle of free education, says Oskar.

Busy?

In the end, getting your degree on time might not be the only goal. Even if both the university, the government and a lot of students see the value in completing your studies in the allocated time, both numbers and experience show that the road through the studies can be bumpy. Life happens – challenges and joyful distractions that not always fit the schedule. Maybe the most important thing is that everyone complete their studies based on their own abilities, with both knowledge and experience that make us ready for a meaningful (work)life?