NMBU: A university of sustainability?

NMBU: A university of sustainability?

As an observant student who loves to read, you’ve probably noticed that NMBU crowns itself with the title “University of sustainability”. Why do we call it that? Can we even do that? What happened to the good, old College of Agriculture?

Journalist: Åsmund Godal Tunheim

Illustrator: Signe Aanes

Photographer: William Fredrik Bakke Dahl

Translator: Eva Weston Szemes

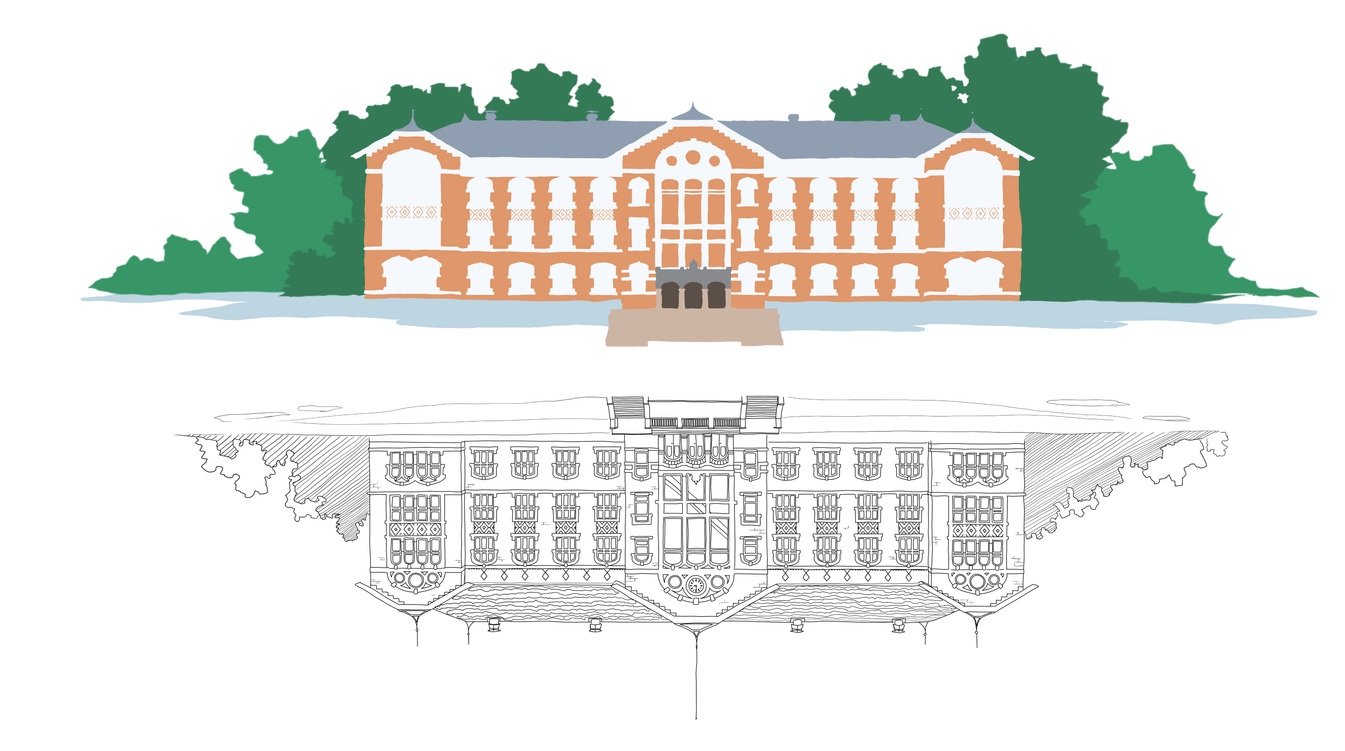

If we go 20 years back in time, we find Ås as a picturesque little village built around a charming little institution of education – NLH: A college highly built on tradition, with space for about 2000 students that has given education in agriculture, forestry, land consolidation, landscape architecture and food science, and a few more fields, for more than 100 years.

In 2024, sustainability is the thing. On their website, NMBU advertises with “…studies and research that meet the big global questions about environment, sustainability, better health for people and animals, climate change, renewable energy sources, food production and the managing of areas and resources.” The rector’s right-hand man is ‘vice rector for sustainability’, and millions of NOK is spent on communication to promote us as a green university. Now, we are almost 8000 students, and almost 1000 of us study sustainable economics online.

Here, we have to take a look at history to find out when, how and why ‘sustainability’ benched agriculture. I went to the top floor at Sørhellinga to find the answer: The two previous rectors Hans Fredrik Hoen, rector 2010-2014, and Sjur Baardsen, rector 2019-202, let me into the office a snowy Thursday in April and started explaining.

Sustainability turned into a popular term back in 1987, when it was used in the UN-report “Our common future”. It was defined as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” According to Hans Fredrik and Sjur, NLH already knew this word from forestry, where the attitude is that you should be able to keep the forest alive forever, by making sure that new trees replace the ones that are cut down – and this is also found in the mantra that the farmer should always leave his farm in better condition than when he took over. Because of this, they think this term was already well known at the college.

Until the 60s, NLH was a scientific college with five agricultural lines. A lot of people thought NLH was a “college of agriculture” with close ties to agricultural organisations. Even though we were independent, this pushed a wish for modernisation and expanding the fields of knowledge. The 70s presented the studies “Land Planning” and “Natural Resource Management”, and the studies in economy and technology were renewed in the 90s.

“Remove the farmers”

In 2003, colleges could apply for university status, and NLH was quick to turn in their application. In 2005, the board consisting of professionals from both Norway and abroad concluded that we were worthy, and UMB was established. The possible alternative meaning of the abbreviation (Remove The Farmers) quickly turned into a joke, but at least it was official: “Agriculture” (Landbruk) was switched to “Life Science” (Miljø- og Biovitenskap), and the sustainability focus was established. As a university, UMB had the privilege of establishing new studies – and a lot of new studies were established. These were mainly sustainability oriented. At Noragric, multiple new studies emerged, with an increasing focus on the global challenges in society, with a comprehensive, interdisciplinary focus. Other studies were also established, like ‘Public Health’, ‘Renewable Energy’ and ‘International Environment and Development Studies’.

In 2008, new problems emerged. Stjernøutvalget proposed some radical changes in the structure of Norwegian tertiary education. They highly recommended that all institutions of tertiary education with less than 5000 students be combined with other institutions. In Ås, this was a concern, because at that time, we were only 3000 students. “At that point, we put the pedal to the metal,” Hans Fredrik says. Between 2008 and 2012, we also received multiple batches of financial support for more students. This led to multiple new lines of study, and space for more students in general.

“It’s really time to remove the farmers” was on everyone’s lips when NMBU got its current name after the fusion with the School of Veterinary Medicine in 2014. We wanted to be relevant for the whole country, and at the same time keep the term ‘Life Science’, and this is around the time that the nickname “Sustainability university” emerged for the first time. But how could we, in teeny-tiny Ås, deserve this description? If we look at the strategies of the other universities, they are very similar.

The group that worked on the strategy plan for the new university, led by Mari Sundli Tveit, focused on the fact that this institution was rigged to find answers to the big global challenges. “From 2015, when UN published their report with 17 goals for sustainability, it would be stupid to not say that WE are the sustainability university, but also work towards it.” Hans Fredrik says. Sjur adds that this is also about finding our place in the pack of competing universities.

Just for show? During his time as rector, Sjur and his vicerector Solve Sæbø were working on a system that could show how the 169 intermediate goals impact each other and simplify them to a more manageable level. The system was called “The Sustainability Portal” and was also meant to show which intermediate goals was covered by the different courses at NMBU. “This way, we could show the new students in a concrete way why we are the ‘Sustainability University’, and we wanted to know which intermediate goals and interactions between them the students were taught about,” Sjur says. Unfortunately, this initiative was not continued once he ended his time as rector.

“It’s essential that NMBU as a sustainability university knows how the different Sustainable Development Goals impact each other,” Sjur says. For example, if we focus on solving the energy crisis by developing renewable energy sources (intermediate goal 7-2) only by hydropower, this will harm life in the rivers and ecosystems on land that get flooded. Only focusing on certain goals or intermediate goals could be detrimental to other goals.

Sjur is highly critical of companies and firms who pick out a few of the goals, and then proudly proclaim that they are sustainable because they get a good score on those goals. “This is greenwashing, if they don’t also tell us how they impact other goals negatively,” he says.

“As a sustainability university, NMBU should be in front when it comes to the work of making sure we fully understand how the system works, how we’re doing today, and how we can turn more sustainable all in all,” says Sjur, and points out that there are many opportunities to go in the right direction.

Sustainable enough? When I ask Sjur what he thinks about the use of an external PR-agency to promote NMBU as a sustainability university, he thinks we should encourage our own people, rather than pay someone else to do it. “We do have a vice rector who has mapped our sustainability skills, and we have a lot of knowledge about sustainability-related topics, but I am not so sure if we understand the whole system.” Sjur ends with pointing out that: “The most important thing NMBU can do as a sustainability university, is educating people with sustainability in their heads. People who understand sustainability, and can act accordingly.”

In under ten years, we went from being a college of agriculture with a few thousand students to a sustainability university with more than 5000 students. The big global challenges are on the agenda for both students and employees. That’s why NMBU tries to attract new students with this campaign: “Do not study at NMBU… if you mean that most of the worlds problems will be solved within five years”.