Greetings, my name is Ottar Brox

Greetings, my name is Ottar Brox

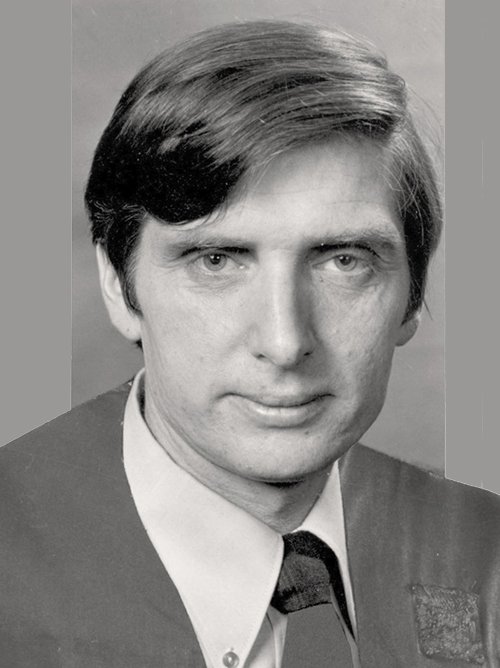

What can one say about a man like Ottar Brox? One who has made his mark as much in the public debate as in research. A colossus who is known far beyond the park areas of NMBU. Yet, he had both feet firmly planted on the ground, always ready for a lengthy conversation with the editorial team which he led nearly 70 years ago.

Journalist: Martin Hansebråten

Journalist & fotograf: Tord Kristian F. Andersen

Translator: Vegard Sjaastad Hansen

Ottar started in Tuntreet in the autumn of 1955, as member 102 of the editorial staff. In 1956, Ottar became the editor of the student newspaper. This period was characterized by a playful spirit and postwar joy, but also hints of the more serious issues that occasionally cast a shadow over the humour. Ottar recalls his first issue as Editor, in January 1956, with great pleasure: “It was done quite professionally, both as a student and as a journalist. Those are the things that make me a little proud when I look back now.”

Tuntreet’s publications were highly variable. Brox explains that it could take “anywhere from three weeks to three days.” At that time, there was a commitment to 10 issues per year, but the size of the issues could vary from 12 to 28 pages, typically around 20. The releases were not coordinated with exams: “There was often a collision between what had to be done...” “And what one wanted to do?” Tord interjects. Ottar laughs and nods in agreement. The production of Tuntreet was very busy, leaving little time for each individual article (much like today).

Brox worked to ensure that Tuntreet was a less pretentious newspaper. “We tried to include as much humor as possible in the magazine, but not everything was childish,” he says with a laugh. Not taking things too seriously was, in part, a reaction to the content of other student newspapers: “The number of Latin words should not be the determining factor. “ Nevertheless, Brox himself was ambitious when it came to academics, admitting to occasionally making a fool of himself because of it. Otherwise, Ottar thoroughly enjoyed working at Tuntreet, and he had actually intended to become a journalist. Jakob Kringlebotten, the founder of Tuntreet, stated in an interview for the 25th anniversary of Tuntreet: “Personally, I think Tuntreet had a particularly good period in the mid-50s. Ottar Brox impressed me. The debate material during his editorship was excellent.”

It was very common to write under pseudonyms at that time. Even with firm opinions it could be challenging to be exposed with a full name. “The main writer was often the editor,” Ottar explains. Thus, he may have had the most pseudonyms. “But many were eager to write.”

Several people from Tuntreet later entered journalism. Brox mentions Andreas Vevstad as one of his classmates and editorial team members who continued in journalism. He later became the editor of the professional magazine ‘Norsk Skogbruk’ (Norwegian Forestry). “Many had their professional careers influenced [...] by editorial work in Tuntreet,” Brox explains.

“It was not uncommon for us to have a bit of an inferiority complex because we didn’t write really serious material.” “That still lives on a bit,” Martin says. Ottar explains that Tuntreet still had a more consistent quality than many of the other student newspapers. (Editor’s note: this remains the case.)

ukeREVUES

Brox tells us he helped make two UKErevues at Ås, when he was a first year, and third year student. He starts singing the song ‘Høyskoleproffen’ from the UKErevue ‘Ku vadis’ from 1950. He sings:

“Vaskemaskin fikk fru nabo av sin Proff da han kom fra U-hu-S.A.”

He helped make the revue ‘Rustica’ from 1956, whereupon he sings a tune from the song ‘Alma mater grisen’. He continues:

“Det var da je traff a’ Alma hu var budeie hos’n Sjur […] Nå har a’ Alma begynt å falma men for meg ... (osv.)”

Ottar says he was the lead author of the song, but when he heard it again on a radioshow with student-songs later on, someone else had gotten the credit for it. At this, Martin reveals the name of the miniUKErevue to Ottar and Tord two weeks before it’s official release. “Har du hørt at”, or “Have you heard that...?”. Woopsie. The volunteer involvement of Ottar covers a vast amount of time, and he was knighted by Hestehoven in 1970.

‘Greetings, my name is Brox’

Ottar tells Tuntreet that he was also the secretary for the rowing association, ‘Ta det med Roklubben.’ He mentions he was never selected, but was involved solely because his last name was Brox. For those unfamiliar, one of the memes of that time was ‘Greetings, my name is Cox.’ This originated from a highly popular series of NRK radio plays in the 1950s. “It was so INCREDIBLY funny,” Ottar says sarcastically, while Tuntreet’s correspondents try not to tinkle themselves (Because it was really funny).

Difficult decisions

Som student var det mange vanskelige valg som måtte tas. Det fremste er kanskje det som ble utgreid i utgave 8 i 1955. As a student, there were many difficult choices to be made. Perhaps the foremost was the one elaborated upon in issue 8 of 1955. The question was about the use of Samfunnet’s “Mathall” (Food Hall), which we believe was located in parts of what is now Johannes. By using this offer, one could avoid one of life’s great dilemmas: “There you can avoid the difficult decision of whether to eat four or five meatballs,” as Brox responded back then. “The everyday problem, such as the number of meatballs; it’s clear that it deserved to be addressed,” says Brox in 2024.

Professors, pals and ladies

Brox recounts that most professors could just as well be regarded as fellow students. He mentions that there were a few academic snobs, but remarkably few: “There was incredibly little exaggerated academicism. I could have mentioned two or three individuals, but it’s unnecessary to single them out after so long.” Most were involved in debates and social gatherings at Samfunnet.

Ottar speaks fondly of his good friend Kåre Lunden, who later became a renowned historian. Ottar mentions that Kåre specialized in the period between the Black Death and April 9th, 1940.”If there was any academic among us in that cohort, it was Kåre.” Kåre Lunden was also part of the editorial team at the same time as Ottar. He explains that Kåre was one of the most prolific writers for the newspaper during that time. Brox praises his academic abilities and especially highlights that he was a very versatile athlete.

We also asked Ottar about the number of women at NLH at that time. He explains that there was a record of eight women in the joint class of a total of 70 students in his cohort. In the 1950s, there were three classes, totalling around 200 students.

Life after studying

What Ottar Brox is most known for is his work as a politician, public debater, and author. One of his predecessors, Helge Solli, wrote about many of the same topics and was instrumental in establishing “Rural Sociology” at NLH as a separate subject. However, Ottar believed that Helge was thinking too intricately. Perhaps that’s why Ottar spent so much time writing books on these topics with a broader appeal.

Ottar served in the Norwegian Parliament from 1973 to 1977. During his tenure, he was a member of the Maritime and Fisheries Committee and the Municipal and Environmental Committee. He was also a substitute member of the UN General Assembly.

“What’s Happening in Northern Norway?” is his most famous work. The book was published in 1966 and discusses the challenges of industrial development in Northern Norway. Brox believed that industry and jobs should not be imposed from the outside, as was largely done through the Labour Party-led governments in the post-war period, for example, through the national development of hydroelectric power and power-intensive industry. He argued that Northern Norway should rely on local resources, primarily fish, which has enormous value in itself. “What’s Happening in Northern Norway?” was named one of the most important Norwegian nonfiction publications of the post-war period in 2008, placing him alongside authors such as Arne Ness, Hanna Kvanmo, and Thor Heyerdahl.

Emigration, largely due to the trawler industry, remains a huge problem for Norwegian coastal communities. Brox predicted many of these challenges as early as the 1960s. He believed that the fishing industry should be based on small boats and was a staunch critic of the current quota system, where large trawlers are allocated fishing rights at the expense of coastal communities.

His arguments apply not only to the fishing industry in Northern Norway. The idea that a local area should be based on local resources and people, rather than something imposed from outside, is universal to all small communities. Similar problems are found, for example, in agriculture, where large farms are becoming more common. In addition, he put on the agenda that Northern Norway is not just an economic loss project, but that it actually produces something of value.

Even though he has been active in public debate and has done important things “in the real world,” the conversation always returns to his student days. Ottar says he has benefited greatly from his time at Tuntreet. He places less emphasis on the works he is more famous for. “I have written some thin little books,” he says humbly. He continues that Tuntreet was a very important developmental period for him: “The period as editor was crucial for what I would spend my time on afterwards.”

Just under three weeks after this interview was conducted, Ottar Brox passed away. He remains one of the truly great NLH students; someone who truly had the ability not to let a debate die out, but to keep it going and bring it to the national agenda. He had a unique ability to communicate, not only in Tuntreet, but also in Norway and the wider world. Ottar may be gone, but the Broxian perspective lives on. Good night, Mr. Brox. Thank you for everything.