Tuntreet decade by decade: the 50s

Tuntreet Decade by Decade: the 50s

The 40s is over and done with, so I do continue into the slightly more optimistic 50s. I notice that after four years in the press, Tuntreet’s childhood diseases has been curated, and the 50s did in many ways become a middle phase for the paper. People saw a brighter future after the war ended, but the political involvement hadn't yet reached fanatism as it did in the 70s. As Lars Raaen said: “The students were involved in politics, but wasn't as “rebellious” as the generations to come.”

Journalist: Tord Kristian F. Andersen

Translator: Vetle Rakkestad

A Paper for Students and the College

A lot of the content is tightly related to the College, not only relative to the contributors, but also the college’s content. In the third edition from 1950, it was suggested to split every year into trimesters of 12 weeks. Today’s block system has its main focus on the parallel, but it is nevertheless divided in three (January, spring and June), and it is exciting to see that today’s ideas at NMBU was discussed already back then.

In the same edition, you will find the answer from a group of students to what the ideal housewife’s education should look like. “A male only having exams from high-school would have inferiority complexes if he picked an academician as life companion”, is one of the statements. Another rumbles “Education... what a nonsense.”

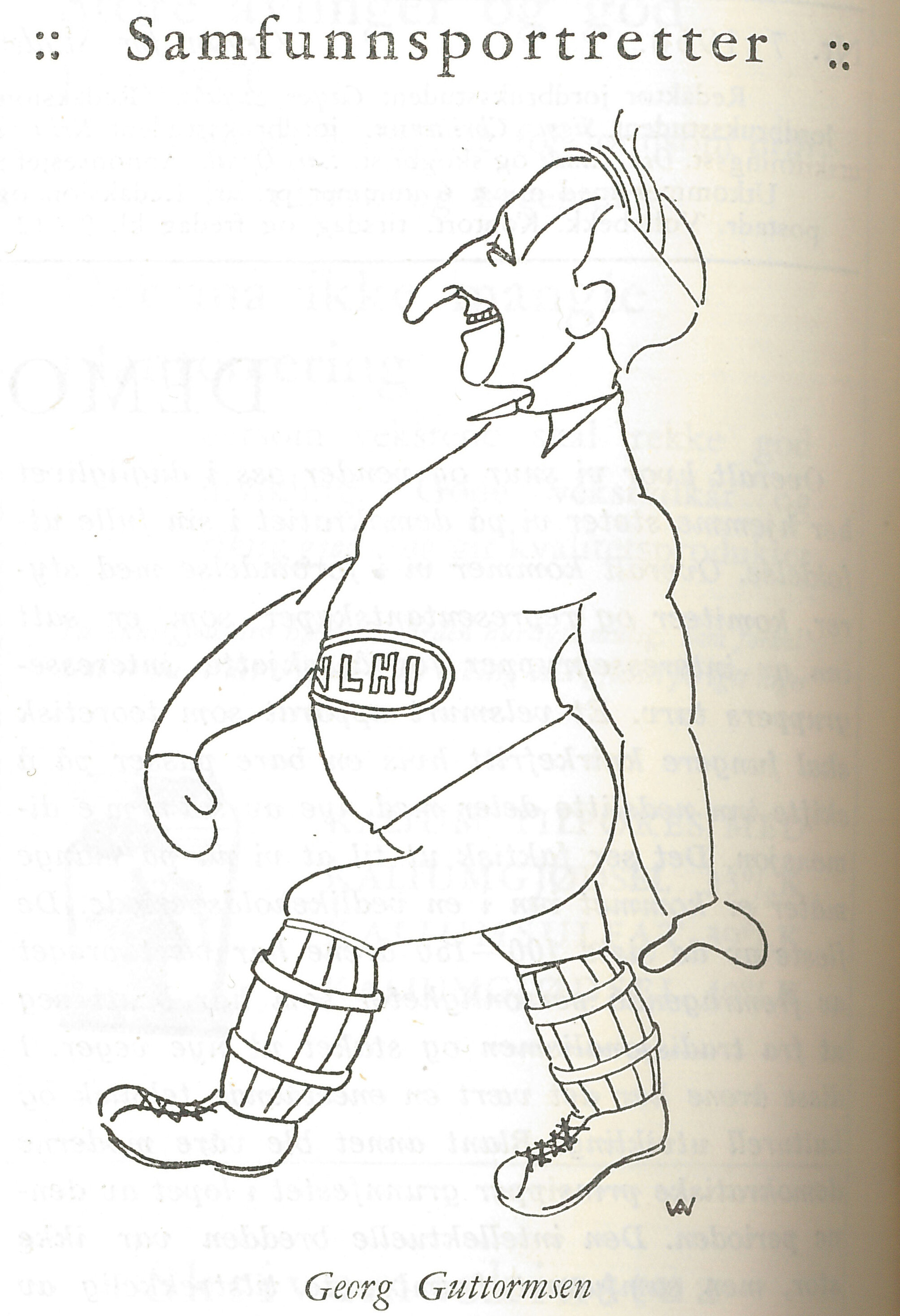

Society portraits, and the voluntary work at Samfunnet and UKA is also given a lot of coverage in the paper. It could be interviews, poems, posts from readers, and a lot of other formats. Preferably with a caricature of the author.

As in the previous decade, I also here notice a few positive posts strongly similar to those in today's editions. As an example, “the first hepatica nobilis of the year” is the reflection of “the last dandelion of the year”. Who would believe that seven decades separate them? Despite the fun and interesting above, there is one thing that can be said for certain; these old editions are more similar to ordinary papers compared to today's editions.

How Was This Done in Practice?

To expand my knowledge, I called Halvor Holtestaul, an involved student, and SiÅs’s first CEO who told me that everyone read Tuntreet in the 50s. He studied between 1956 and 1959, but subscribed to the paper for many years succeeding 1959. At the time, Tuntreet could be perceived as Samfunnet’s paper for members, and was included in the membership without further cost. This decision was made by the House and Finance Board March 17. of 1950. Tuntreet was both delivered to the mailboxes belonging to members of Samfunnet, and other non-members with subscription. In many ways this made the paper work as a public forum for everyone with an affiliation (especially) to Samfunnet, but also NLH.

The editorial staff consisted of six to eight journalists, and was, as now, guided by an editor chosen by the general assembly. The editor was the one who employed the editorial staff. From 1949 an editor secretary joined the group. This was a position with a large variety of tasks, as editorial changes and to keep an overview over the product bounding for the press amongst others. This position was held until 2004, when it was substituted by a leader of proofreading. The school did only have about 230 students in the 50s. A more tied environment, its role as a forum, together with the smaller group of editorial staff shows that the paper has been greatly dependen on external contributions. And contributions there was! Tuntreet thus played a role in the discussion in both politics, religion and society.

The creative process leading to a new edition of Tuntreet is elegantly described in the appropriately named article, “An all-out effort”: “The paper is published in six to eight all-out efforts a year.” Some things doesn't change very much.

Other remarks

After a look through the whole decade's edition, I have noted that Storebrand was opened January 7. 1950, the same year as “the large amount” of five ladies was matriculated at NLH. Universitas was discontinued for a period in 1953, while the development of NLH continued, with a proposal for a new building on Sørhellinga in 1955. In the Nazi journal Folk og Land there was a text about Samfunnet in 1956, and the recurring discussion about Christians took place in 1959.

A small hint of cold war can be seen between the everyday and larger events. A post is written about hoping that the Korean War was not too distracting throughout the summer to shadow over the roads towards a fantastic UKE. UKA was of course a huge subject every UKA-year. While writing about UKA, I can’t resist to directly cite the leader for the revue group of 1950, Helge Løken, from fourth edition the same year:

“We who have experienced an UKE will never forget it. When we in our exam periods or other boring times of our lives want some bright memories and funny episodes to look back on, UKA is usually the first thing that appears in the memory”

To summarize, Tuntreet in the 50s proved that Samfunnet actually could keep a paper alive, which was a major question beforehand. This means that people were sufficiently involved, both readers and editorial staff. The content is varying greatly, with only a fine border between nonsense and the more serious content. At least I do appreciate this variety. To be able to view the state of affairs with a cross eye makes it a whole lot more interesting than just ascertaining the state of affairs. And what the state of affairs really is, becomes more and more subjective as politics plays a bigger role, so I strongly recommend you follow along in the next Tuntreets “Decade by Decade”.